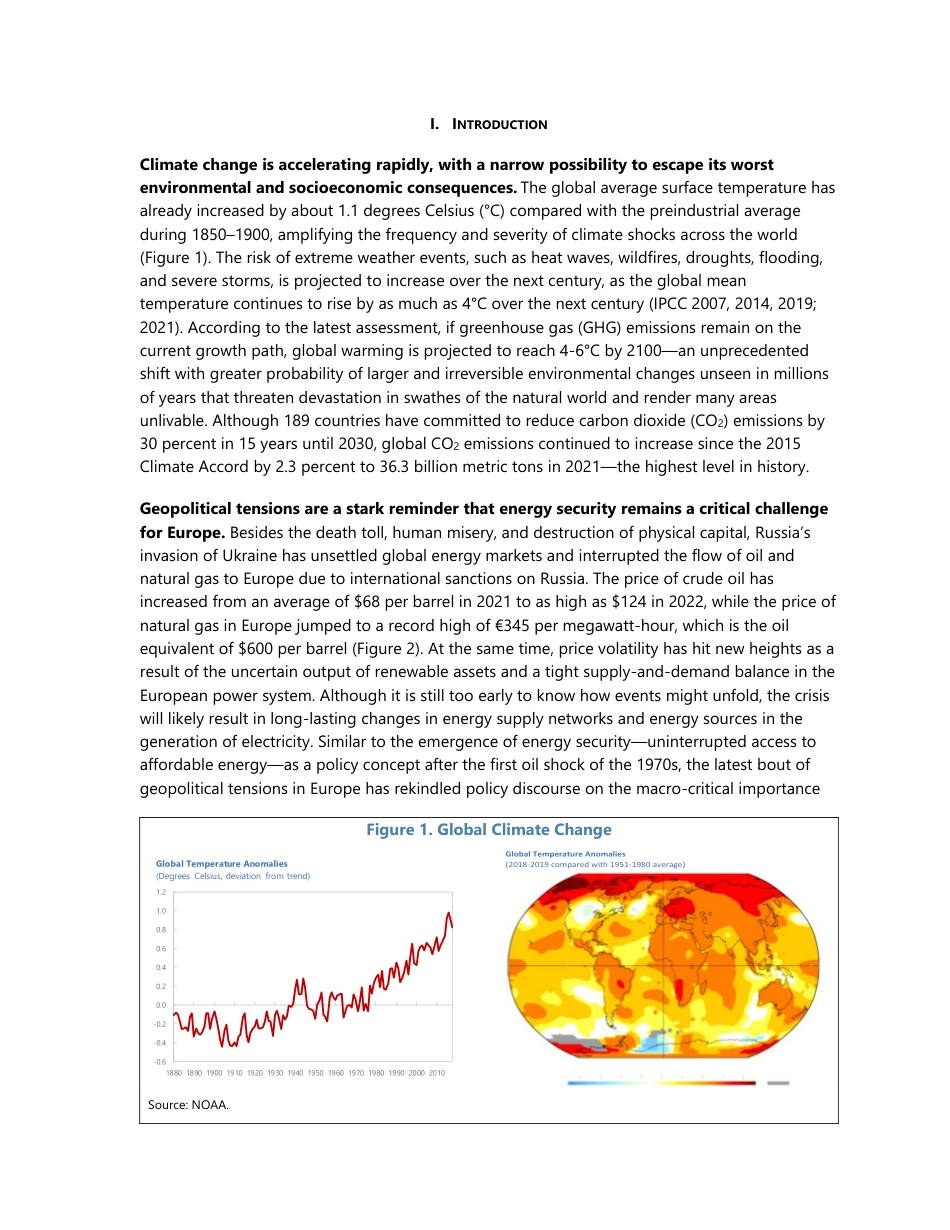

2022 SEP Climate Change and Energy Security: The Dilemma or Opportunity of the Century? Serhan Cevik WP/22/174© 2022 International Monetary Fund WP/22/174IMF Working Paper European Department Climate Change and Energy Security: The Dilemma or Opportunity of the Century? Prepared by Serhan Cevik1 Authorized for distribution by Alfredo Cuevas September 2022 IMF Working Papers describe research in progress by the author(s) and are published to elicit comments and to encourage debate. The views expressed in IMF Working Papers are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of the IMF, its Executive Board, or IMF management. Abstract This paper investigates the connection between climate change and energy security in Europe and provides empirical evidence that these issues are the two faces of the same coin. Using a panel of 39 countries in Europe over the period 1980–2019, the empirical analysis presented in this paper indicates that increasing the share of nuclear, renewables, and other non-hydrocarbon energy and improving energy efficiency could lead to a significant reduction in carbon emissions and improve energy security throughout Europe. Accordingly, policies and reforms aimed at shifting away from hydrocarbons and increasing energy efficiency in distribution and consumption are key to mitigating climate change, reducing energy dependence, and minimizing exposure to energy price volatility. JEL Classification Numbers: Q43; Q47; Q48; Q54; Q55; Q58; H20 Keywords: Climate change; energy security; carbon emissions; energy efficiency; Europe; transition economies Author’s E-Mail Address: scevik@imf.org 1 The author would like to thank Borja Gracia, Gee Hee Hong, Ian Parry, Hugo Rojas-Romagosa,...